Des explores some ways in which communication can help to either establish, build or diminish Trust

In 1981 Kirsty MacColl sang about deceit, plaintively reproaching her sweetheart: “I can’t help feeling that, somehow, you don’t mean anything you say at all.”11 She mirrors how we all judge other people’s levels of (dis)honesty – by their words and actions. Centuries earlier the first Poet Laureate, John Dryden, claimed ‘Truth is the foundation of all knowledge, and the cement of all societies’1.

But, if it’s difficult to believe anything a liar says, what should we make of research which suggests most of us lie at least once or twice a day – though normally with positive intent2. How can any of us ever be trusted? The fabled Boy Who Cried Wolf wasn’t believed when it finally mattered most. He got eaten by said wolf, teaching us all a valuable moral lesson: nobody believes (or likes) a liar. If Kirsty’s chip shop “Elvis” offered advice about defeating a global virus pandemic, we probably wouldn’t pay him much attention. We’re not aware he possesses specialist subject expertise, and we suspect him of dishonesty anyway.

Both are important considerations for us all. If we want to persuade people to think differently or take a particular course of action, it’s critical that we first establish our credentials and credibility, to make them trust us. That’s true in politics, in workplaces and in life in general. It’s GPB advice based on c. 2,400 years of thinking and research. Aristotle believed establishing trust-worthiness is a foundation upon which all persuasive communication is built3. His view is now supported by modern research which reconfirms that successfully appealing to Ethos (establishing you can be trusted and relied upon) is a prerequisite for effective persuasion4.

Other aspects of communication also help develop an audience’s trust. These include the words you choose, the way you say them, how you look when you say them and whether these things all consistently match your other words and actions – and people’s overall perceptions of your character. Can we really believe you will deliver?

Truthfulness is essential for establishing long-term Trust. We mislead people in the short-term at our peril. If we’re not thoroughly believed, persuading others to think or act our way will be difficult, regardless of our carefully reasoned arguments. We also need to genuinely believe in our own words and ideas. Otherwise, we risk revealing give-away signs – or “tells”- about the truth. Professor emeritus Paul Ekman claims that body and facial gestures, including ‘micro-expressions’5, help to reveal our lies. The proverb ‘Fool me once, shame on thee; fool me twice, shame on me’ suggests we should and do learn to read others. Sometimes the hard way.

We all continually assess whether or not we like and trust people. If we hope to influence others, this makes it vital we ensure the impression they form of us is a positive one. A poor first impression might leave your audience forever wondering whether you can really be believed at all – and trusted to get things done.

Perhaps Dryden was wrong, or his ‘cement’ of social cohesion failed somewhere along the way. Since, these days, we’re unsurprised that even a placid Thought For The Day presenter can blithely state “it’s rare to hear public figures apologise for their mistakes, or take appropriate responsibility for errors of judgment”6, without exciting controversy or outrage.

It’s now commonplace to suggest that politicians, in particular, don’t routinely tell the truth2. Or, at least, not the whole truth6. That’s a significant factor in why so few establish lasting credibility and trust. Yet we might not even be entirely sure why it is we don’t trust them.

Senior politicians are routinely coached, rehearsed and scripted. Yet this can create issues, as well as sometimes solving their short-term difficulties. ‘Spin Doctors’ advise them what questions to avoid answering. Sometimes they provide specific phrases to use – and to avoid. This might help control the message, but rarely helps create overall positive impressions. Terrified of saying (though apparently not necessarily of doing!) the wrong things, politicians normally avoid answering tough interview questions, instead responding to imaginary ones they would rather be asked.

They’re sometimes also coached to use a limited, repetitive, sterile, glib vocabulary, which further erodes Trust. As does the appearance of being slickly rehearsed. Humans generally prefer spontaneity, honest answers and admissions. We want to form positive impressions of interesting, real people; ‘warts and all’. In a recent pair of short, consecutive interviews7, however, Matt Hancock (UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care) demonstrated this robotic narrowing of vocabulary. Using a few carefully memorised phrases repeatedly, in line with his planned, defensive Key Messages (e.g.: “Vast Majority” – 6 times; “Operational Challenges” – 5 times) his delivery was jarring and seemed unnatural. Mr. Hancock is used here purely as a topical and representative example. He is very far from being a lone culprit.

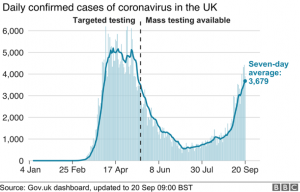

In those same interviews, Hancock also described as “broadly flat” what could already be recognised as the recurrence of a steep, upward Covid-19 infection trend. If you choose points on a timeline carefully enough, of course, many negative trends can be disingenuously described as being broadly flat. Just two weeks later, 13.5 million Britons were under renewed local lockdown restrictions. With more to follow, soon after.

Oops! Political advisers seem unaware that, when their chip shop Elvis makes misleading claims, they risk alienating audiences. Who might henceforth discount the likelihood that anything else they say is true.

Kier Starmer, the latest ‘new’ leader of the UK’s Labour party, suffering a credibility crisis of its own, recently admitted (astutely and honestly) in an interview, “First, we need to rebuild Trust”8. Luckily for him, there are ways of successfully developing trust and positive impressions, beyond simply telling the truth. For example, handling tough questions well can build your credibility. And that’s something we can all practice. This normally includes actually remembering to answer all parts of the questions asked, where possible. As suggested earlier, however, many politicians experience great difficulty in doing this.

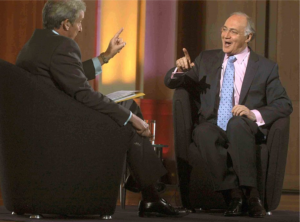

For example, in a live 1997 interview, Home Secretary Michael Howard once famously refused twelve times to answer a simple question. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his party leadership bid soon floundered. The UK might very well look a rather different place now, if only he had felt more comfortable handling just one awkward question.

Presenter Jeremy Paxman admitted much later that he’d persisted with this “rude” farce of questioning after discovering his next scheduled interview on the show had fallen through9. Demonstrating it’s not just politicians who are sometimes economical with the truth. The erosion of Trust can be a slippery and dangerous downwards slope for us all.

One final example I’ll share here is of a fictionalised historical statesman: Shakespeare’s Mark Antony. The Roman General, politician, and (later) Triumvir, Consul and lover of Cleopatra misleadingly claims, ‘I come to bury Caesar, NOT to praise him’10.

Kirsty McColl might well have commented, whilst raising a suspicious eyebrow: ‘…But he’s a liar / And I’m not sure about you’11.

After all, would you ‘lend Mark Anthony YOUR ears’ – and trust him to ever give them back again?

By Desmond Harney

References

Quote sources:

- Google Books. 2020. The Works Of John Dryden. [online] Available at: <https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=GTIrAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA17&dq=The+Character+of+Polybius+(1692)&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwizj9mqsITsAhVyQxUIHRsCASAQ6AEwAHoECAYQAg#v=onepage&q=The%20Character%20of%20Polybius%20(1692)&f=false> (Transl. by Henry Sheeres – Page xvi).

- DePaulo, B., 2020. The Devious Art Of Lying By Telling The Truth. [online] Bbc.com. Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20171114-the-disturbing-art-of-lying-by-telling-the-truth>

- Sam Leith “You Talkin’ To Me?” (2011) Chapter: The First Part of Rhetoric.

- Petty, Richard E.; Cacioppo, John T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387963440.

- Paul Ekman Group. 2020. How To Detect Lies By Analyzing Facial Expressions. [online] Available at: <https://www.paulekman.com/blog/how-to-detect-lies-by-analyzing-facial-expression/?utm_source=mailchimp_Sept23.20&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=paul&utm_content=analyze-face-sept-20&utm_term=deception&mc_cid=5732e27c62&mc_eid=d485e42bb2> [Accessed 25 September 2020].

- The Guardian. 2020. Brandon Lewis Breaks Cardinal Law For MPs And Tells The Half-Truth | John Crace. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/sep/08/brandon-lewis-breaks-cardinal-law-for-mps-and-tells-the-half-truth-john-crace> [Accessed 25 September 2020].

- 3rd September, 2020: BBC R4 – Today programme; BBC1 Breakfast TV

- BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, 21/9/20

- ‘Michael Howard finally reveals why he wouldn’t answer Jeremy Paxman’s question’ – by Jack Maidment, The Daily Telegraph, 31 August 2017

- Julius Caesar, by William Shakespeare: Act III, scene II — line 73

Image sources:

- ‘There’s a Guy Works Down the Chip Shop Swears He’s Elvis’, co-written and sung by Kirsty McColl https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v4HFAztX27s (with track link)

- https://fanart.tv/fanart/tv/82548/tvthumb/would-i-lie-to-you-5699e55169b48.jpg

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-51768274

- https://www.thearticle.com/the-paxmanisation-of-political-interviews-has-not-made-them-better/.

Dowload a full PDF version of this journal here: GPB 74th Journal – Autumn 2020