A stoic view of trust

To be ‘stoic’ is generally to be considered calm in enduring hardship. What did it mean originally?

I stumbled on the Stoics during a bit of background reading on Aristotle’s better known appeals to persuasion. I was not expecting what I found.

The ‘Stoics’ were something of an extremist group founded in Athens and Rome in the 3rd Century. Its simple and accessible philosophy was that Aristotle had not pushed out the boat quite far enough on the importance of Ethos based on logic, and that Pathos, in particular the show of negative emotion, was a bad thing to do: One should live one’s life developing good character, to be tranquil and not get angry, sad or moody about one’s lot. Stoicism was made to be easy to understand.

We often get asked by clients about becoming more effective as communicators, and we often end up discussing good character, gravitas, seniority, authenticity and integrity, and how we can use sometimes simple techniques to become more persuasive. To go right back to a founding principle of GPB from over 25 years ago, one key goal we set in our work is to help clients get across ‘an accurate yet positive impression of yourself’. Put most simply, the philosophy underlying Stoicism was to help people to be the best person they can possibly be, living the best possible lives.

Not only is it possibly a way we should all lead our lives (but see later), I can see a direct read across to the events in the UK Parliament event last week. I have not heard the word ‘stoic’ used there yet, but if someone there suggests the ensemble should be a bit more ‘stoic’, you may well support the suggestion! Very much in the vein of ‘calm down dears, it’s only a commercial’, but without being patronising. I would also espouse the song ‘Happy’ by Pharrell Williams. Do go and play the song if you’re feeling a bit blue today. The version in Despicable Me 2 on YouTube is particularly good!

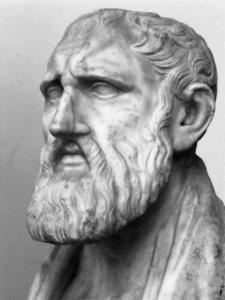

Although the founder of Stoicism was Zeno of Citium, the group did not end up calling itself ‘The Zenoids’, as it transpires that even he did not sustain his good character in living up to the group’s rather tough set of rules; they eventually threw him out as leader and member (more read across to UK Parliament there too?).

Let’s consider how this all might apply to the modern business world that we live in:

To start with, trust – and the lack of it we have in most other people – is becoming ever more important. The ability of a business developer to gain the trust of a potential client has always been important, but recently it seems to have risen above the use of logic and emotion as a first check-point in the development if this relationship. We first determine whether we can trust someone, and if so, we let them pass to the points where we determine if we like someone and if we think they have a good persuasive case.

In business, we rely a lot on the integrity and honesty of the counterparties we meet. This is because decisions about the future involve taking a leap of faith (about which we have written before) in the people who we will be relying on, whether it is to manage a pile of money, to give us healthcare and medicines, to advise us on courses of action, to look after our children, or to check our accounts so that stakeholders get a true and fair view of our company’s fortunes.

Sadly, so often when we read of the people in these positions of trust and authority, it is to learn that they have abused the trust we put in them, despite in many cases being self-regulated, and that is why we have so many regulators. Regulators for example for our money and investments (FCA and PRA), our auditors (FRC) our water (OFWAT), our teachers (TRA), and, and… some 90 regulators in the UK alone.

But we also have very good sensors for when we are being misled – bulls**t detectors if you will – and I have been wondering what might trigger these sensors. Let’s start with identifying them.

It is well known that we have 5 senses, that see, hear, smell, taste and touch. No we don’t, there are several more such as pain, heat and proprioception that often get overlooked. But in the analysis of trust sensors, I think the important ones are see, hear, and to a lesser extent, touch and smell. Here are some thoughts on each of these:

Smell: This shouldn’t be a factor, but if we sense someone has B.O. (body odour), then their personal hygiene leaves something to be desired. They may be nervous or have hurried as they were late, and we may then not respect them so much. B.O. is an unpleasant smell, so causes dislike. By contrast, nice perfume (as measured by the smeller not the smellee), has a pleasant effect. Antiperspirant does also have value!

Touch: We don’t do much of this in business, so when we do touch, for example with a handshake, it takes on an importance that is out of proportion. This greeting must be firm but not painful, dry and not sweaty, and just the right length. Again the main reaction is on the pleasantness axis.

Hear: This is more important. If we hear a high level of disfluencies, above 5 per minute (4 categories—umms/errs, repetition, fillers and hesitation), then we quickly determine that the individual is underprepared, lacks knowledge or conviction, is nervous, or uncertain. At over 12 per minute we add unpleasantness to the perceptions. None of this will help with building trust. This is especially true when handling a client question, where we are well able to sense a faltering answer.

See: The other important sense. If someone does not have enough eye contact, or has tells such as rubbing their hands, or is sweaty, the negative effects are similar to those of hearing.

Note too that trust is a very fragile thing. It can take a long time to build and be destroyed in an instant through one careless act, even after years of careful construction by you and others. So take special care of it.

Conservative MP and author, Kwasi Kwarteng (before you write in, yes he did go to Eton, Cambridge, and Harvard) was interviewed recently on the subject of (dis)respect for the police and teachers. He identified a societal problem: the young today do not have deference but happily disrupt, disrespect and question everything. He suggests this started in TV in the 1960s with seeing the worst in figures of authority, e.g. the change from Dixon of Dock Green and Z cars to The Sweeney.

Their view is supported by the Macpherson report on Stephen Lawrence: police are institutionally racist. But… Hackney schools have turned attitudes around since 2002. Kwarteng suggests that the solution not just more police on the streets, but also for those in authority, such as teachers, to behave better and thus to develop greater respect and trust.

Here though is a twist on Stoicism: It has been shown that emotion is not only an important part of persuasion, but that perhaps it is THE most important part. That does not suggest to me that Stoics got it wrong though, as it seems it is more the display of positive than negative emotion that is important here.

If you think back to some recent decisions you took, consider whether the real reason was a logical one, or whether it was really an emotional one, that may not pass the test of enquiry, so it was post-justified by a logical case that you can share as your reason. I suspect you can think of at least one hiring decision where like/dislike was a factor. There is no shame in that, as emotions are very important in making good decisions.

Download a pdf of the article here: A stoic view on trust