The importance of explaining “why” when communicating.

The ability to explain “Why” could well prove to be your most valuable super-power. A recent Harvard Business Review article1 claimed that good leadership is about doing precisely this, particularly in a crisis. How very topical! Although it seemed to lean quite heavily on the essence of Simon Sinek’s best-selling 2011 self-help title, ‘Start With Why’2.

At GPB, we wouldn’t disagree with that principle, but our own advice goes much further. Whether during a crisis, after one, or at any other time, we’re convinced almost all successful, persuasive communication involves explaining “Why”. Whether you’re a leader or not. Reflecting that belief, I’ll now explain why, in the hope you’ll find some of our advice and thinking helpful.

In the seminal Negotiation text ‘Getting to Yes’3, Harvard University’s Ury and Fisher observe: ‘to accomplish our work and meet our needs, we often have to rely on dozens, hundreds, perhaps thousands of individuals and organisations over whom we exercise no direct control. We simply cannot rely on giving orders – even when we are dealing with employees’.

Empowered audiences naturally ask themselves “Why?”, when asked to act or think differently. From a positive perspective, this at least means they’re engaged: proactively searching for answers, explanations, or a rationale.

This presents opportunities to provide answers and disarm potential challenges, which might otherwise undermine your persuasiveness.

Communicators sometimes fail to explain “Why” because they think the answers are self-evident (certainly to themselves, ‘obviously’!). That they’re so apparent, no further clarification is necessary. But typically it is needed.

For maximum persuasive impact, we should ensure our messages – including the reason(s) “Why” – are Clear, Concise, Complete and Candid (the Four Cs).

They should also be constructed to be, and to appear to be, credible, logical, and ethical – because you’ll probably want to be believed, understood, and approved of. Ask yourself: why do you need to communicate? What action or change in thinking do you require? Your answers should help you start selecting and building the best, most relevant possible communication content. Remember that the answer to “Why?” normally starts with “because…”

Most people do things for their own reasons, not for yours. So, to persuade them, it’s important to give good reasons they can align with, and maybe even consider to have been their own.

As Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel laureate noted for his work on the psychology of judgment, decision-making, and behavioural economics, says: “the remembering self composes stories and keeps them for future reference… we all care intensely for the narrative of our own life”.4 We have a chance to help construct and illustrate people’s personal narratives for them

If you compose clear and complete stories, whilst providing strong reasons “Why”, you make it much easier for your audience to accommodate and remember your request/requirement.

You helpfully reduce the cognitive load demanded by thinking things through and deciding whether or not to agree.

By contrast, for instance, if you rely instead on your leadership position (on your authority, status or power) then, although you might seem to get the actions or answers you want, you’re likely to be gaining only the appearance of agreement and conformity.

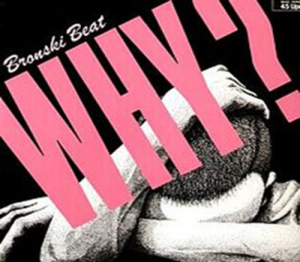

Jimmy Somerville’s unanswered question, from 1984.

Reluctant participation can create resentments – delivering sub-optimal, mixed results and storing up potential trouble for later. While persuasively explaining “Why” can help avoid such difficulties and achieve several other aims, too.

Doing so can make you appear more ethical and likeable. These are important factors in being persuasive.

Taking pains to explain and give good reasons for your own thinking gains you credit. Giving powerful messages as to “Why” makes your communication more memorable – “stickier”.

Answering the “Why” well should involve providing the best evidence you can muster. Your strongest possible argument is likely to be formed by a combination of several different types of evidence, since this will appeal to the widest interests of the audience. If you know them well, however, you might even weight the use of specific evidence to best suit your audience.

Wherever possible, use supporting evidence that suits your personality. Don’t stray out of character. You should use a combination of:

Facts, Data, Statistics, Examples, Images and/or Quotations. Whatever material you choose, your factual evidence must as far as possible be correct, authoritative and verifiable.

Do research to ensure your evidence is accurate. Don’t get anything wrong, which might leave you open to challenge. For instance, be sure any supportive quotes from relevant famous people are correctly attributed – like the one I’ve used from Kahneman!

At GPB, when we talk about different Behavioural Styles, we advise that, to be persuasive, you should treat people the way they need to be treated. That advice has a corollary here: understand your audience, and talk to them the way they need or like to be talked to. Explain “Why” in THEIR language and terms. Doing so should make gaining acceptance for your key messages easier and longer-lasting.

Your arguments (usually forward looking) should be well grounded in logic and make sense, even if they’re initially surprising to your audience.

Providing strong counter-arguments to perspectives they may hold and which you’ve also considered can help demonstrate how much you’re on the audience’s wave-length, building even more common ground.

Big issues you’ll need to communicate persuasively in the short-term, either internally or externally, could indeed include the impacts of Coronavirus and the economic downturn.

Why? Because, following lockdown, your organisation is unlikely to return immediately or entirely to its old, pre-Covid ‘normal’ ways of working—and maybe it never will. You’ll need to decide on and clearly communicate WHAT any ‘new normal’ should look like and HOW that will be achieved by your team.

But you’ll also need to explain WHY any proposed changes are the right and best things to do. And, to maximise both your impact and credibility, we recommend you communicate consistently to all potential stakeholders. It’s a pattern most communication should follow, anyway, most of the time.

To maximise alignment, consider other people’s self-interest. By all means explain WHAT you need from them and HOW they’re going to deliver that (the Features).

At least equally important, however, is explaining WHY that will be of benefit – to them, not to you. Fundamentally, you should show how your proposal affects them for the better: the positive impacts – or least negative.

In 1972, Johnny Nash sang that “There are More Questions than Answers”5 But nearly 50 years on, in reality, an effective communicator tries to provide all the necessary answers, in order to explain “Why”, to get their audience ‘on board’ and to minimise the risk of meaningful challenges.

By Desmond Harney

Other sources:

- HBR: Good Leadership Is About Communicating “Why”, Nancy Duarte – May 6th, 2020 edition.

- ‘Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone To Take Action’, Simon Sinek, 2011

- ‘Getting to Yes: Negotiating an agreement without giving in’, Roger Fisher and William Ury (Preface to the Third Edition)

- ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’, Daniel Kahneman, 2011 (Penguin edition, p.387)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johnny_Nash

- https://www.ambyrne.com/2018/01/17/hollywood-keep-making-super-hero-movies/).

- https://houston.culturemap.com/news/city-life/07-12-10-a-rebranding-crime-village-people-respond-to-the-ymcas-name-change/).

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Why%3F_(Bronski_Beat_song)

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Y.M.C.A._(song)

Download a PDF version of this article here: Tell me “Why?”