By Lynda Russel-Whitaker

Jumping on the ‘neuro’ fever that has had the UK in its grip for more than a year now, I’ve been reading a lot of research on ‘neural plasticity’ or the malleability of the brain. New findings are indicating that our brains remain very plastic well into adulthood.

The thing is we actually know that we can adapt; the evidence is all around us. Not just when we’re children, but as adults. Think how our habits and behaviours have changed over the past 15 years. With the advent of broadband, smart phones and ever smaller and more powerful PCs, we have shown our remarkable ability to adapt and learn new skills.

It’s probably axiomatic that the brain’s plasticity would be important to those of us in the field of training, so imagine how frustrating it is when people – clients in particular – say they can’t change their behaviour, or learn something new.

In a now widely published research study from the year 2000 conducted by [neuro]scientists at University College London, London black cab drivers were proven to have an enlarged posterior hippocampus.

The average 3 to 4 years’ training to pass ‘The Knowledge’ clearly has a dramatic effect on their brains. As Dr Eleanor Maguire, who led the research team, said “there seems to be a definite relationship between the navigating they do as a taxi driver and the brain changes”.

She added: “the hippocampus has changed its structure to accommodate their huge amount of navigating experience.” We all benefit from that!

This touches on the area of memory, which is what I’d like to focus on in this article. Hopefully, you’ll be able to exploit the plasticity of your own brain using the techniques in this article, especially when having to pitch, present or give a speech.

Although our brains are more malleable when we are children, the environment and the techniques used were also designed to help us learn and retain information.

As author of the highly-acclaimed ‘Guitar Zero’ and psychologist at New York University, Gary Marcus, says, “The idea that there’s a critical period for learning in childhood is overrated”.

That being said, there are clearly aspects of childhood learning worth carrying into adulthood. According to a study on the acquisition of foreign accents by Yang Zhang at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, we may simply be suffering from poor tuition!

In his article on learning like a child, David Robson of the New Scientist magazine asserts that external testing makes a huge difference to retention. So perhaps our tendency as adults to self-test in the workplace should be curbed.

Clearly, working with a coach and rehearsing with trusted colleagues should be encouraged, as this form of ‘external testing’ can greatly enhance the quality

of a presentation.

I touched on the use of the simple mnemonic device of rhyme as a way to improve memory in my article ‘Rhyme or Reason’ (SpeakUp No. 44). Mnemonic devices are visual or verbal techniques that make it easier to remember seemingly unrelated information.

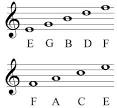

Learning to read music as a young child, I can still recall another popular mnemonic device, the acronym, I was taught to remember the notes on the lines of the treble clef:

For contrast, “FACE” seems to manage well enough as a method for learning the notes in the spaces, and for the sake of completeness, mind-mapping is another useful example of the brain’s amazing ability to be malleable.

As a way of bringing dull or dry data to life, mnemonics often work by evoking vivid and unusual imagery and emotions.

Furthermore, many studies show that combining words and pictures in our heads improves our recall as well as our understanding.

These devices will not only help you learn important facts and figures, they will help you retain them longer and recall them quickly. Useful when faced with a challenging questioner on the opposite side of the table!

Of course, the prevalence of smart phones not only shows us how adaptable our brains are, but how lazy they can be too. When was the last time you committed a number to your own memory, rather than that of your handheld device?

A useful technique to recall a variety of data, especially figures with more than 10 digits, is chunking. Separating, or chunking, the figures into groups of 3 and 4 (as we often do with phone numbers), seems to be the most efficient way to memorise them.

Repetition and writing them down helps of course, but the point is to train your memory rather than refer to a piece of paper or your mobile.

There are several habits worth retaining from childhood, including openness and curiosity. Perhaps most important is the willingness to make mistakes – perfectionism being the scourge that truly impairs our progress (and probably our joy too) as adults.

Once we liberate ourselves from the need to get something perfect, we find that we can learn and retain new information in the way we did as children.

Speaking personally, I learnt to read, write and speak Greek to a very high level in less than 3 years when living there, because I gave up trying to construct every sentence perfectly and just enjoyed playing with the language.

“Είναι όλα τα Eλληνικά μου”

“It’s all Greek to me (In Greek)”

So the next time someone you know says “I’m too old to change” or “I’ve never been able to do that”, remind them that old dogs as well as young ones can be taught new tricks!

Note: The cognitive scientist, Ed Cooke, has a website (www.memrise.com) devoted to mnemonics should you want further inspiration!